DANIEL McHORTON was born in slavery sometime in the 1840s in Augusta, Ga. Hattie Maria Corrin was born in comfortable circumstances on October 23, 1864, in South Coventry, Conn. In the early 20th century, across the lines of race, gender and class, the lives of these two remarkable people intersected. The result made a difference for hundreds of African American children in Augusta for generations.

Emancipated in 1865, Daniel McHorton could read and write by the time he appeared in the 1870 census. Perhaps his former owners had given him the gift of literacy. After all, according to his story, he had protected the females and family property during the Civil War and made the shoes his owner’s son wore to the front. By 1870 Daniel had married Silvie and they were raising two unrelated children, the first of many they would take in. Daniel later explained that he and Silvie loved children, but never had any of their own. He was also by 1870 the owner of a 20-acre farm worth $400 on Butler Creek several miles from town.

Throughout his life he continued to work his farm and remained active in organizations for black farmers, including the state Colored Agricultural Association. A man of service, the 1873 board of education report showed that Daniel McHorton also taught school for African American children in his district. Active in the local Republican Party, he ran unsuccessfully for office in 1872. By 1884 he had become pastor of Spirit Creek Baptist Church, a position he held almost 30 years. υ

Hattie Marie Corrin spent her early years comfortably acquiring a private-school education. But the mid-1870s depression and the subsequent death of her father brought financial reversals to the family. She married Lester Lockwood, moving with him to Tacoma, Wash., where in 1892 their son Lester Corrin was born. When Corrin was only five, his father deserted them, leaving Hattie alone with a small child and no money. Divorcing Lester in 1897, she pulled herself together and travelled with a friend to Gold Rush territory in Alaska to open a hospital/hotel for sick and injured miners. Shipwrecked in a blizzard off the shore of Skagway, the women lost their entire investment in medicines and supplies, and almost lost their lives. The determined Hattie stayed in Alaska for a time supporting herself with various jobs. By 1901 she and Corrin appeared in the Canadian census.

Will a Christian city like this allow these poor children to freeze to death for want of bedding?

Seeking a milder climate for her health, she settled eventually in California where she met and married the widowed Henry A. Strong, co-founder and first president of an exciting new business of the era—Eastman Kodak. With his own children grown, Henry adopted Corrin and the family settled in his home in Rochester, N.Y., where Eastman Kodak was headquartered. The Strongs had a happy marriage, but the trials of Hattie’s previous life had honed both her determination and her empathy for others in difficult circumstances.

In 1896 the Shiloh Baptist Association of African American Baptist Churches in the area, founded an orphanage in Augusta named for its first manager, Gad S. Johnson. In a time before financial safety nets, especially for African Americans, the need was great. Although Augusta had the Tuttle-Newton Home with its endowment for orphaned white children, African American children had no corresponding refuge and many “waifs” ended up in the streets. When Johnson’s controversial management of Tuttle-Newton ended and he left for Macon, the board turned to the respected Daniel McHorton to reorganize. With the new name of Shiloh Orphanage and well-known African American citizens, including A.R. Johnson and William J. White, on the board, Shiloh assured the public that this home would be properly run. Under McHorton’s management, the orphanage began operation in late 1899 with 12 children in a house on Sherman Street near Railroad Avenue. They started completely from scratch without even plates for the children’s food. By February 1900, there were 22 children at the home. McHorton sent an anguished cry to the community for help with the basics: “Will a Christian city like this allow these poor children to freeze to death for want of bedding?” He also solicited donations of wood, shingles and bricks to add some space. Black community members were doing what they could, but as McHorton pointed out, “our people are poor and therefore we appeal to our good white friends who are more able to help us.” It was a plea that he would repeat many times over the ensuing years.

McHorton was enterprising and had no intention of relying solely on donations. In the fall of 1901 he sold a bale of cotton, which he and the by then 32 children had raised on vacant land near the house. His hard work and self-sacrificing conduct won the support of the newspaper. In May 1902 an editorial entitled “A Worthy Charity-Reverend Daniel McHorton’s Colored Orphanage” noted that the institution had not received the support that it deserved but predicted it would “as soon as fully understood by our people.” McHorton wanted to acquire four to five acres near the city on which to build needed structures and to cultivate the food and crops that would help them become self-sustaining. He also wanted the children to get an education in the basics and to acquire marketable skills. The article pointed out that he was managing on eight cents per child per day in addition to some donations of food. The Grand Jury responded by donating $5.50 and some merchants donated bricks and lumber with McHorton vowing to build when he had enough. “I can but promise,” he wrote, “to do all I can to make this home a credit to our city and people.”

By the summer of 1903, 51 children lived at the home with 12 on the waiting list. By fall the institution had made the first payment on new property in the suburb of Harrisonville. That season the children and staff of the institution had picked 7,000 pounds of cotton and 14,000 pounds of peas for area farmers to earn money. They had also planted more than five of their eight acres in vegetables for their own sustenance. In spite of this they asked both white and black churches to think of them “in this hour of need” for shoes and warm clothes for the oncoming winter.

Through fire, flood, depressions and wars, Shiloh survived until the 1970s…

By 1905 several older boys worked on McHorton’s farm on Spirit Creek to produce additional food for the many mouths the institution had to feed. On the orphanage grounds were the small buildings where the McHortons and children lived, some built by the boys. The boys had also built a blacksmith shop where they learned that trade and carpentry. The girls contributed by cultivating the gardens and sewing, washing and cooking. In spite of the hard work, the children were loved by Daniel and Sylvie who worked alongside them and did everything they could so the orphans “would know they were not forgotten.” One reporter from The Chronicle wrote in 1905 that when he saw the children gathered around Daniel, “I knew I had beheld a vision of the Good Shepherd.”

In 1904 the Shiloh Baptist Association bowed out, saying they could no longer sustain their support. Refusing to abandon their children, the McHortons soldiered on alone, continuing to work hard at being self-sustaining and cultivating the support of the Augusta community—black and white. They held open houses so the public could see firsthand both the hard work and the acute need. In a few years, as delinquent payments on the mortgage loomed, McHorton’s pleas became more desperate. In January 1908 The Augusta Chronicle opened a subscription list for people to rescue Shiloh. The debt owed was $2,700, but the owners were willing to be patient if they received a $500 payment. Throughout the month donations came in with names such as J.B. White, Landon Thomas, George Butler, Paine College, Planters Cotton Oil Co. and Cumming Grove Baptist Church appearing on the donor list. As a result the crisis was averted—at least until the next payment was due on the remaining $2,200. Meanwhile, the regular needs and expenses of the day-to-day operation of the orphanage made it difficult to accumulate any surplus.

The devastating flood of 1908 drained much of that year’s charity dollars, so by winter the orphanage, up against regular needs and another payment on the property, was again facing possible dissolution. Among the winter guests in Augusta at that time were Judge and Mrs. William Howard Taft, invited by their friends Landon and Minnie Thomas. In mid-January 1909, as the soon-to-be U.S. President prepared to leave Augusta, he accompanied Minnie on a visit to Shiloh. A month later he described his experience in a speech in New York: “I tried to be dignified…but I did need my handkerchief before I got out.” Taft sent a donation and a note of commendation, boosting the hope and morale of the McHortons. Perhaps more importantly, he aroused the interest of a charismatic Northern visitor.

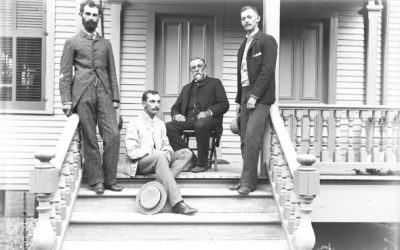

The winter of 1908-1909 was the first time Henry and Hattie Strong had come to Augusta for the “season,” now that son Corrin was in college at Yale. After the Taft publicity, Hattie Strong inquired about Shiloh and Minnie Thomas took her to visit. Hattie said that after meeting Daniel McHorton and seeing the children, she couldn’t sleep. She sprang into action, determined not just to make the year’s mortgage payment, but to also eliminate the entire debt. In addition to her own donation, she prevailed upon fellow tourists at the Bon Air, Hampton Terrace and in private homes in Summerville. One of the first to comply was John D. Rockefeller, who by that time rarely made personal donations, having established a foundation for his philanthropy. Minnie Thomas raised $200 at a children’s musical given at her home. Within one week $3,160 were raised, enough to pay off the mortgage and build a new school building.

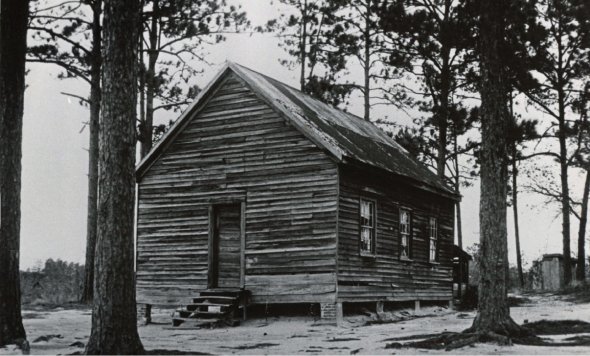

A grateful Shiloh hosted a praise service for the work that The Chronicle called “one woman’s winter in Augusta.” Held in front of the school house under construction, visitors from the Bon Air and Hampton Terrace, along with some of Augusta’s own, heard recitations from orphans Abraham Lincoln and Napoleon Bonaparte and delighted in the naming of the school—Strong Academy. A formal dedication of the completed structure took place that April and in August a portrait of Hattie Strong was hung. The Strongs continued to support the school with their efforts and finances. Henry became a member of the board and after his death in 1919, Hattie took his place.

Daniel McHorton died in May 1913. He and Silvie had raised almost 100 children at the time of his death.

Support also came from Augusta’s African American community as well as many of the town’s leading white citizens and organizations. The day-to-day operation of the home, without an endowment, remained a constant fundraising challenge for Daniel McHorton and his successors. Through fire, flood, depressions and wars, however, Shiloh survived until the 1970s when social service programs sent child care in other directions. The site, however, then got a new life as Shiloh Community Center under the energetic, self-sacrificing leadership of Mrs. Ruth Crawford. She and Daniel McHorton were kindred spirits.

Daniel McHorton died in May 1913. He and Silvie had raised almost 100 children at the time of his death. His work lived on for generations, for over the years hundreds of orphaned or neglected children found a caring home at Shiloh. Without the timely help of Hattie Strong, however, his best efforts may not have been enough. Hattie lived until 1950, devoting her life to philanthropy—supporting hospitals, educational institutions and social service organizations in the U.S., Europe, Asia and Africa. In 1928 she founded the Hattie M. Strong Foundation, which still operates to provide scholarships and grants to institutions training teachers.

Hattie Strong would go on to donate buildings to many institutions including Peking University in China, Rollins College in Florida, the University of Rochester, Salem College in North Carolina, the YWCAs in Rochester and Washington D.C., and a hospital in France for disfigured veterans (for which she received the Legion of Honor). But Strong Academy at Shiloh Orphanage was her first effort, inspired by the compassion and unselfish dedication of Daniel McHorton—the legacy of them both.

Dr. Lee Ann Caldwell is an Augusta historian, author and director of the Center for Study of Georgia History at Augusta University.

This article appears in the February-March 2016 issue of Augusta Magazine.